Uriel Orlow, Geraniums are never Red, 2016-17

Interview

with

Uriel Orlow

Geraniums

Are

Never Red

Interview with Uriel Orlow

by Dimitrina Sevova

D: Is there a metaphor behind the title of your personal exhibition at Corner College, Geraniums Are Never Red? How would you contextualize the title in relation to your ongoing long-term project and research Theatrum Botanicum?

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums are never Red, 2016-17. Detail. Photo: code flow

U: It is also the title of one of the works in the show – even as such it’s not exactly metaphorical but rather counter-intuitive in that we know geraniums as being red. So it produces a kind of hesitation. Why aren’t they red? Or: What’s the problem? It goes back to the misidentification of what we know as geraniums by the first settlers in South Africa. The Dutch brought them back to Europe, and they were called African geraniums. But they are in fact, pelargoniums. Geraniums, biologically, are never red. Pelargoniums can be red for sure. It’s a small detail, but also very telling. In the meantime, so-called geraniums have become quintessential alpine flowers on balconies of chalets, and are also very common in California. They have been around for such a long time that they’re not considered migrant flowers anymore. They are naturalized. When, some 100 years after they were first brough to Europe, it became clear that they were misidentified, the name was not changed back. Geraniums were big sellers, and people had already got to know them as geraniums. So this piece also points to the larger concerns of my work in relation to plants and politics and history which are explored in different ways in the various works that make up Theatrum Botanicum.

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums are never Red, 2016-17. Installation view. Photo: code flow

D: It surprised me when, through your work, I became aware that geraniums are not native continental European or alpine flowers. I had always associated them with a eurocentric and conservative value, even a kind of bünzli (Babbage) taste. It seems that these flowers have long been appropriated by the narrative of the nation-state, not only in Switzerland. For example, in Bulgaria they are widely spread and also have a strong presence in late 19th and beginning of 20th century national literature as a symbol of the Bulgarian house. Funnily enough, they are proclaimed the most Bulgarian flower of all.

U: They relate to what can be called botanical nationalism, to the way plants are related to ideas of nation, to the image of a nation. The fact that we consider them quintessentially Swiss, or bünzli, is also a kind of projection. I’m interested in how plants have come to be instrumentalized in these kinds of projections.

D: How do you approach the botanical world as a stage of history and politics at large? To what extent can the botanical world be connected to a prerogatively human construction like history, which is always problematic? History is also the notion of time, which can produce a gap that allows different temporalities to pass. How do you work with the heterogeneous series of independent times to generate another history, and what kind of politics can be constituted by the botanical world?

Discussion between Uriel Orlow and TJ Demos at the opening of the exhibition, 1 April 2017. Photos: Lisa Biedlingmaier

U: Conventionally, we think of history as human history, as what we do, events that we cause or experience. And humans are of course the main actors in this history. Sometimes, major natural catastrophes may enter history but the main actors are always humans. So to me, it seems interesting to think about history not just from the point of view of humans, but also from a botanical perspective, considering plants as actors in and witnesses of history. There are trees around today that have already been around five hundred years ago.

I made a work, called The Memory of Trees, which is not in the exhibition, but is specifically about trees, and what trees have witnessed in South Africa: for example, a tree that was used as a location for slave trading, or a tree that was used more recently, during the anti-Apartheid struggle, as a kind of identifier for a safe house for activists who were fleeing from the security forces. Trees, and plants, are connected and embedded in history. But it’s not just about plants as witnesses and onlookers. I’m also trying to think about plants as active agents in history. This allows an oblique view of history, a sideways look at history. Especially when it comes to violent histories like that of South Africa, it seemed useful to me to approach it in a different way, which is not just to do with events, but also with how we engage with the environment and the environment engages with us. This opens up a longer-term temporality; organic time, cyclical time, multi-dimensional time and multi-species time.

D: How long have you been working on your ongoing research project Theatrum Botanicum, of which this exhibition is a part? Why do you prefer provisional aesthetic forms that you re-compose according to the art institution, the exhibition space and the context in which you exhibit your works and actualize specific directions of both your research process and artistic practices?

U: The research started in 2014, about three years ago. This kind of project takes time to develop, to research, work with people, create new communities of collaboration. It’s a cumulative process and I’m exhibiting works along the way. When I show work I also want to consider and engage with the context of where the work is shown, both the city or country, but also the space of the exhibition venue. So the work needs a suppleness so it can change according to each context. I think of it as modular: it can be re-combined in different ways and while the some aspects of the work stay the same, others can change and adapt to local contexts.

D: What method or politics drives your artistic research? Are there defined boundaries between the process of research, your artistic practices, and the display?

U: The research is part of the practice, it’s what I do. The material manifestation of a work, aesthetic, formal and narrative decisions come out of and are in a way suggested by the research itself. I don’t have a preconceived idea what kind of work I’m going to make so that’s why I end up making sound installations, as well as videos, drawings, photographs etc.

Uriel Orlow, What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name, 2016-17. Installation views. Photo: code flow

D: The way you work with the research materials, with the sensitivity of the material intervention, you collect fragments or heterogeneous elements to assemble or disassemble them in often unexpected ways and trace connections or breaks that tell stories. Not in the sense of fiction, as they are not fictional stories, but a sort of fabulation of anthropological, historical or scientific materials and things, an arrangement that creates agency, becomes active to slip out of the visual matrix to find the cracks and the passage – from image to fabulation, which is a political practice, too – and generate lines of dissent that run across the exhibition space, able to force movement, to displace. Your sound installation, What Plants Were Called Before They Had a Name, activates the sonic capacity of care work to make a new web of connections across space and time, an ecology of relations. One can feel that there is no common world, but a cosmopolitics that holds or bonds together in an (im)possible commonality human and non-human, and the voices in the sound installation with the audience, a space of sharing secrets. A kind of other sociality, not only people yet to come, but invisible plants yet to germinate in the exhibition space.

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums Are Never Red. Exhibition view. Photo: code flow

What kind of unmediated knowledge other than the scientific taxonomy is transmitted there? What would you like to make visible, and what should remain invisible in your work? How do you relate the archive material to the present?

U: For a long time I’ve been interested in stories that are not part of official discourse, what I call blind spots of representation. They are present, but we don’t notice them, or they’re not told for some reason. Usually, I don’t tell them in a straightforward way. As you say, it might be more interesting to fabulate them, allowing them to remain fragmentary to an extent, and for the viewer or the audience to put the story together: building blocks that can be re-assembled. This demands an active engagement on the part of the viewers and an ethics of looking or listening. In What Plants Were Called Before They Had A Name, which is an audio piece, primarily, there are no visuals, as such. The work is about the obliteration of existing local knowledge through colonial conquest, specifically through botanical explorations that aimed at naming and classifiying plants. This act of naming, which persists today, produces a continuous obliteration. So I started recording plant names in different languages over a period of two years, with a lot of different people. I wanted to find out how an audio plant dictionary would work? So here, it’s important that there are no visuals for example and no translations: it’s not about creating a new classification, a new kind of access, appropriation or mastery. It’s about staying with not understanding.

But in each case, with each work, the question of representation is newly posed in relation to the specific material. With The Fairest Heritage – where I’m using found footage from the National botanical garden in Cape Town from 1963, it seemed important to show and engage with this archival footage: it speaks about its own time, about botanical nationalism, and flower diplomacy. At the same time it’s extremely problematic footage. So the question was how can these images be shown, and how can this kind of archive be confronted in the present? That is, not just presented, but also confronted and engaged with. That’s why I worked with an actor (Lindiwe Matshikiza) who inhabits the images and confronts their content.

Uriel Orlow, The Fairest Heritage, 2016-17. Installation views. Photo: code flow

D: In the critical questioning of representation in the projection within the projection that undermines the previous status of the footage. It merges the two planes, which actually underlines what can be seen only on the surface of the image. Is there an interrogation or disturbance of the technological dispositive of representation at its meta or ideological level looking not only at botanical history and the colonial past, but also at the history of representation itself and its particular economy of image production in Western culture? Because it seems to me that this piece also decolonizes the field of vision, where the viewer is confronted with the stereotype of their own gaze in a kind of subversive affirmation that ‘destabilizes’ the setup between beauty, femininity and nature, or race, class, sexuality and labour, that manifests as a construction of the spectacle. At the same time, it spiritualizes in the most intense way. If “а science was once founded on the basis of this projection of time onto the space: anthropology” (Nicolas Bourriaud), in a way you are undoing the anthropological predicaments through the performance of the actress that overlays the real, the symbolic and the imaginary, past and present, as both an echo and re-appropriation of the ‘original,’ ‘authentic’ footage material. This new image can be seen as an unconscious of representation in the relation between the image and the cinematic body. A time-image that is not a thing happening in time but a new form of co-existence and transformation. This other cinema, based on time rather than on movements, has a particular way of occupying or taking up space–time, made by hand. A tactile cinema of touching and being touched.

Uriel Orlow, The Fairest Heritage, 2016-17. Installation view. Photo: code flow

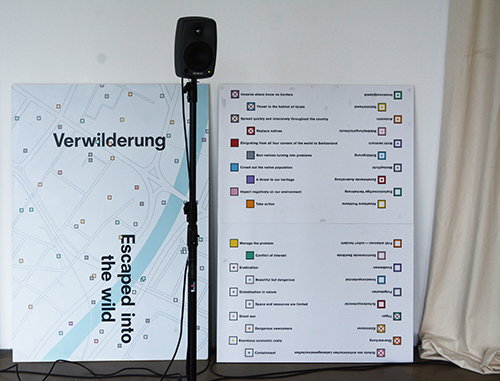

U: That’s a very pertinent reading of the work. There are a lot of correspondences between these questions of representation. I’m interested in one kind of representation also speaking about something else as well as representing or undoing itself. So it becomes a kind of mise-en-scène of a mise-en-abyme. For example in Blacklisted, which looks at the so-called problem of invasive species in Switzerland, the language which is used to describe these plants, and the problem they pose, is part of the work and questions its own means of representation. It’s found in books about plants, yet it’s not just about plants, but also speaks to how we think about the world, how we think about place and who has the right to be here and who doesn’t; who is seen as an intruder.

Uriel Orlow, The Fairest Heritage, 2016-17. Installation views. Photo: code flow

Uriel Orlow, The Fairest Heritage, 2016-17. Installation views. Photo: code flow

D: Can you say something about your approach to cartography and maps as a form of abstraction in your new piece, Blacklisted (Was wir durch die Blume sagen), to talk about invasive species in relation to the official discourse and the language of legislation used to describe illegal migration? The German expression in parentheses, literally: What we say through the flower, refers to saying something in a roundabout way. In the title of this piece, once again there is a flower as an agent that constitutes the space of the idiom. In the relation of language and flowers, it seems to me that flowers play an ambiguous signifier rather than a referent, in a kind of twisted object-subject relation.

U: Maps are machines of representation and abstraction – constantly turning one into the other. A map is a form of control, allowing us to master a place by way of simplifying it. Maps are instruments used in planning and visualising historical or anticipated developments. Maps themselves are a roundabout way of saying something about a place. So a map of invasive plants in Zurich produces a different image of the city: a besieged and invaded city, but also a cosmopolitan city connected to a history of migration and colonialism.

D: To what extent is the journey itself present in your approach to your topics, specifically in Theatrum Botanicum?

By journey, I mean Nicolas Bourriaud’s concept of radicant aesthetics, ‘a global displacement in non-hierarchical and non-specific spaces’ that can be a re-engagement with the environment and specific location/place, or as in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s nomadic thought, a journey of non-linear time travelling that ‘occurs simultaneously in space, time and in the social hierarchy.’ In this respect, what kind of traveller is the artist?

Uriel Orlow, Geraniums Are Never Red. Exhibition views. Photos: code flow

U: Because I make work in different places, it is important to me that I have a long-term engagement and relationship with a place. It’s never just a brief visit producing a kind of tourist gaze. I try to stay for longer periods of time and return repeatedly. Of course, I’m still an outsider. I’m not from that place. The durational, ongoing nature of the research journey is an important aspect of the work.

Perhaps there is another category that is not the tourist and not the traveller but something else. Something like a guest worker, or a temporary resident. Of course, this still implies a lot of privilege but it comes closer to the periodic duration of being in another place to work.

D: The guest worker can be associated with economic labour under conditions of permanent immigration, Gastarbeiter in German. Mobility and precarization of labour conditions signify globalized capitalism. What about the commitment and resistance of the artist as a guest worker in temporary immigration?

U: If we take the term literally, it means you are a guest in a place and this affects how I work. I rely on people’s generosity and hospitality to get anything done. I’m vulnerable and rely on solidarity. My work would not exist without this. In turn, this also produces a commitment to a place and its people, an interconnectedness and a solidarity in the work itself.