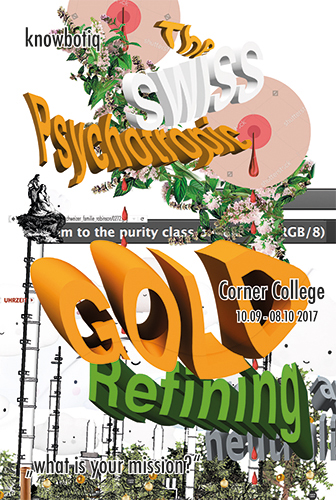

Flyer for the exhibition. Design: knowbotiq

Interview with knowbotiq (Yvonne Wilhelm & Christian Hübler) by Dimitrina Sevova and Alan Roth

Preliminary Edit (for the Finissage)

Dimitrina: When we think about what we would like to know, and make more accessible for the audience, we have four main questions. Let me summarize them from the beginning, and then in the process I hope we’ll have a more dynamic situation in which we may have additional questions on the basis of your exposé or statements.

Yvonne: We don’t talk with one voice, we have some differences…

Christian: We have different views on the project…

Dimitrina: That’s very good… Of course, we would like to have some insights into your process of working together, so that’s a good beginning. For us it’s a kind of collective authorship, of working not only the two of you as knowbotiq, but also inviting other people to collaborate with you in different projects, and especially in this one where you have three more collaborators, or even more, you will tell us how many people are involved, how you collaborate with them. This idea of collectivity and producing a work which is so complex.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Opening, 2017-09-10. Middle and bottom, performance golden acupuncture / charming the ghost points by Martina Buzzi. Photos: code flow

This is connected also to the other question, which is about the complexity of the work. It’s not an installation, perhaps something like an apparatus. An exhibition as an apparatus, your work as an apparatus, it’s not only visual, not the idea of looking at something and perceiving it, but the idea of the work of art as an apparatus as in Walter Benjamin’s The Author as Producer, where he discusses a new complexity in which the work has many entrances and many exits, and so many layers, a complexity of media. In an earlier conversation with Christian, we also discussed the exhibition as infrastructure.

Then of course the main topic, and how you approach it, gold, liquidity, many small questions.

We also have a question within that about your method of political and historical fabulation, working with historical materials, archives, but then fabulating it, the fictional and the use of analytical techniques that become parapraxis, in the sense that you use fiction to fictionalize historical materials. We would like to know how you apply these methods. We know historically how it comes, probably via the Bergsonian-Deleuzian idea of fabulation, but fabulation is older, going back even to Plato. He used it slightly differently, but it’s a kind of envelope via the event, a notion that also comes from Plato.

These are our four main elements of the construction of the interview. I’m not sure which should come first. We can reshape the four elements together.

Christian: I think we have each a different voice. So it doesn’t matter… I think, when I hear these questions, ten years ago, I would have answered them “correctly,” and simulated that I had good answers to them. They are quite meta-questions. Why do we collaborate? How do we collaborate? What is the format? What is the theme? What is the method? It would be easy to give a very concise answer to these questions, because I think it’s always shifting in-between different ways, and different states, and this transition in-between, and the motivation why we do this, what drives us to use certain tools, a certain format, and go into certain constellations with people, has maybe changed within the last years, I would say. It has a lot to do with our personal life forms. It becomes more and more friendship-driven in terms of who we collaborate with. But as an artist, this is always a form of survival, and you have to develop your project, but also your life forms. I’m interested in whether there is a certain affinity and friendship within it. And besides this friendship, there is also a political perspective.

The starting point for this collaboration was an invitation to do a project about Zurich. Once again, since we had done a previous project some years ago, Black Banz Race (2006-2009), which was about Kosovar communities in Zurich. We were asked to do a work about Zurich, and we said, if we are to do that, we have to work about Priština, and Belgrade, and so on. So we developed a project which invents Zurich out of Priština, Bari, Belgrade. Then came the second invitation, and this time it was not only to think Zurich translocally, but I came across this postmigrant discourse, and I heard Rohit Jain speak, and Kijan Espahangizi, and these people are really interested in constituting a kind of new community, a communal being within the city in which different voices should participate. I was very interested in their approach, how to constitute, in a post-colonial and post-migrant context, another kind of political space in the city, or maybe also within this country. The other thing was that when Rohit was talking about his research it was very very close to our thinking which we had developed some years ago with Kosovar migration movements and practices within Europe. This was the starting point for this collaboration, and then within the development of this project other people, other friends joined. Because we have certain questions, and certain desires. But there’s not really a concept at the beginning that we want to work with this specific person or that person. As the project develops, you come to certain crossroads where it’s good that certain persons cross your path and question the stability you assume you have established within the project.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Opening, 2017-09-10. Performance molecular listening session by DJ Fred Hystère and Nina Bandi. Photos: code flow

Yvonne: I think it’s a kind of production that we had. It’s not like we were saying we want to realize an exhibition. We mostly have a topic, and that’s what we start with. We don’t know where it will end up. We like to have some exhibitions, of course, it is part of our practice. But it might as well be a performance, or an intervention in the landscape. It’s not that we decide on a format from the beginning. In that situation, we look for persons to collaborate with on theory, on music, on visual stuff. It’s this kind of open practice in which the topic is at the center. Unlike other artists who prepare a painting exhibition, and put in materiality. Sometimes we are the two of us together, and sometimes we are six or seven. It changes. For us it’s important to have a lot of discussions with those people. It’s sometimes difficult, as it is always a fluid substance of working.

Dimitrina: I suppose the collective authorship is closely related to the fluidity and formlessness you are welcoming in your process of working, experimenting not necessarily with certain materials, or rather you do as well, but a different kind of experiment with material.

Christian: We now have a certain affinity, a certain curiosity, and a certain familiarity with Rohit’s work. But we didn’t know what we would work on with him. You always have to build on what you already have in your baggage. And we have some experience with translocal practices. But then there was also this curiosity on my part about what is really going on with commodity trading in Switzerland. It’s a very opaque business, not visible. We mostly work on themes that are not obviously visible. So one thing was the topic, and then there was an aesthetic aspect as well, which also relates to my infrastructure idea. I came across Kijan Espahangizi’s book about materiality and the materials cycle, Stoffe in Bewegung. In this book, there are several positions. Matter is always in movement, and it’s always transforming and changing, and there are certain ways of thinking about matter in transition and movement. He has some historic lines coming from the metabolistic movement, from circulation and the alchemical thinking about matter, and transforming matter, to cybernetic flows which opened up the global trading of matter, computer controlled and goal-oriented, an economic interface toward matter in transition, and then he ends with the auto-movement of matter (Eigenbeweglichkeit), dissipation and uncontrolled movement of matter itself. We were thinking there is something missing. This was a starting question, how matter is moving. We were interested also in the affective effects of matter, in its psychotropic effects. This was Rohit’s interest, coming also from our first year of research mostly based on interviews, during which we met people in Zurich who were doing research on commodity trading. We approached different key players, like the Erklärung von Bern who published Rohstoffhandel, the bible on commodity trading, enlightening, politically addressing these players, naming them, making them visible through facts, research, crimes, names. The second was Jakob Tanner, a historian who was involved in the Bergier report on Switzerland and WW II.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Opening, 2017-09-10. Performance meditation on pure gold by Gabriel Flückiger. Photos: code flow

Yvonne: It was not that we wished to think about commodity trading out of nowhere. We had an invitation from the Institute of Contemporary Art in Zurich to be part of a research group thinking about art in the public sphere, and also in the political dimension. It was held in India, with ten different cities, and everybody had the task of thinking about their own city, and what are the political issues, and the task for art in the public, to deal with the city. We were part of Zurich, and therefore we had to look for a topic that may be interesting in this context of matter, what you can see, what you can touch and negotiate. But at that point, for us we decided to work on commodity trading, because it’s so important for Zurich, and it’s not visible in the city, so it’s a kind of underground phenomenon. Then we started searching, doing interviews with people from here. And then the people told us it would be good if you worked on gold. Not that there are not other issues, like chocolate for instance, or financial trading itself, but they all said that gold is what is really important.

Alan: Is this specific to Zurich? I know there is a lot of commodity trading companies around Lake Geneva, some dealing not in precious metals but base metals, rare metals you need for mobile phone screens and such.

Christian: They are based in Geneva and in Zug, but the financiers are in Zurich. A commodity trader first has to get money from a bank. Then he buys or rents a ship, buys the commodities, and when he has the revenue he pays the money back to the bank. Guys like Marc Rich came here with little credibility, but got massive money, even with such a bad commercial CV as Marc Rich’s. He was not really creditworthy. But they gave him massive amounts. They really speculated a lot with these guys and trusted them. There was a turn, away from the traditional trading families, who could at some point not cope with the financialization and the kind of trading it brought about, and towards the multinational traders. This was the end of these big colonial families in commodity trading, which lasted about 300 years. The big expert on this is Lea Haller, on the big family dynasties in Switzerland, who hired ships from the 17th century onward and insured the slave traders. With the revenue they founded the first banks in France, and later in Switzerland. They were intermediaries for the colonial players. Among other things, they opened the Indian market to British companies. In our research we found that almost none of the commodities they were trading in appeared in Switzerland. With two exceptions, cocoa for chocolate, and gold for refining. This led us to the decision to deal with one of these two commodities which is materially present. After the first year of researching, we decided for gold.

Yvonne: For us, this research, and dealing in an artistic way with commodity trading, we have done years before with another project, two other projects, we had some experience with that. Then it was not gold, but textiles. It was another project, looking at the role of the Swiss industry in the textile trade. This allows us to connect this project to another we did earlier.

Dimitrina: Is it still like this? Gold is coming to Switzerland? I remember this movie by Oliver Ressler, The Visible and the Invisible (2014), which he showed in Shedhalle, about the new Swiss commodity trading companies, where the commodities are only traded from here, where the companies are headquartered, but never come to Switzerland physically.

Yvonne: Yes, nearly 70% of the gold is running through Switzerland. Five of the biggest refineries are located in Switzerland. They are not in public view, but rather hidden near the border to Italy or France. Gold arrives as raw material, but also as jewelry. It gets refined, and goes back into the circuit of commodity trading. Also in terms of the financial aspects of the trading, nearly 50% of it is in Switzerland as well. It’s a huge topic in the economy of Switzerland.

Alan: Why Switzerland?

Christian: It’s because of the law. Gold can be brought here, and refined, without a need to declare its origin, whether it is blood gold, from which mines, whether there is child labor involved, whether, at the time, it was South African Apartheid gold.

Yvonne: And with the closeness of the refineries to the border there were a lot of possibilities to smuggle the gold, from the Italian border to the refineries and back. In the 1980s the Swiss government decided not to make a declaration mandatory, for fear of disturbing the economic success.

Christian: The refineries are mostly hidden, either in very small villages, inside the village itself in the middle of the living houses, you’ll find a refinery with huge well-guarded walls. Or, like in Chiasso, at one end of the station there is this train station building, and from there a single track swerves off to another direction, directly to the refinery outside the town and towards the border. We went there to record the sounds of the refineries, and saw they are heavily guarded.

Yvonne: In earlier times, the big Swiss banks, UBS and Credit Suisse, had their own refineries, which they later sold.

Alan: On the one hand, you say the legal situation was very favorable, such as the secrecy, the lack of declaration, but nevertheless there is smuggling. How does that fit together?

Yvonne: I read that when you look at the accounting of the refineries, there are some gaps in their usage. It is very difficult to heat the refinery ovens from scratch, so they run 24/7. The usage declared in the accounting of the refineries does not match that.

Christian: And the good thing is that after refining, you can no longer distinguish the origin of the gold. It is neutralized.

Dimitrina: It is then pure gold, universal gold.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Opening, 2017-09-10. Photos: code flow

Christian: Indeed. This was especially important during the embargo against the Apartheid regime in South Africa, which Switzerland did not join. It was then not a UN member, and in return for the South African gold, the Swiss government provided Apartheid South Africa with all that they needed. Nearly all the South African gold came here. It’s fascinating how these protestant people for centuries now have been after gold, even without showing it in the streets. In most of the cases, the gold is not then bunkered here. I think the South African gold is still stored in vaults in London after being refined here. It’s very obscure. There is hardly any information. Then there was the rumor that the gold held by the Swiss National Bank is no longer stored here. It no longer has an economic value or importance for the currency and financial markets. It’s a myth that stabilizes something, and a right-wing, national myth at that, that Switzerland has to keep the gold reserves. Because there is a huge demand for gold from China and Turkey because they need jewelry. Jewelry is a gender thing. Women are given gold, because it ensures they will not be given land ownership. Rather, their gifts remain mobile, and can be taken away, too. Men can also speculate, by lending a woman’s gold and funding their business through the cash generated. Nobody knows how much gold still exists, making it a fuzzy topic. The closer we get, the more the gold is dispersing.

Gold is also used a lot in high technology, in image tracers, in genetic manipulations. There are no longer many nuggets left, i.e., gold in high concentration. Twenty years ago, one used to need one ton of ground to find one gram of gold. Now it’s eight or nine tons of earth or stone that you have to sift through. There is less and less gold to be found. Gold came in from the cosmos as the Earth was forming as a planet.

Dimitrina: In Greek mythology there is this golden rain. Zeus came to Danaë in the form of golden rain, making her pregnant with Perseus. So this has a correspondence in the formation of the Earth, it seems.

Christian: Yes, and the Earth, through the heat released by earthquakes, functioned as a refinery, separated the different metals and condensed the gold into nuggets.

Then we realized that there was yet another movement, from condensing to dispersing. This figure we were looking at, besides the circulation or flow of gold, autopoiesis, is dispersion, and diffraction, which is taken up in the performance by Nina and Anna. We didn’t want to work on traditional topics of gold, not about bullions, bars, solid gold, or gold as a safe haven asset and stabilizing element in the financial markets. We were increasingly interested in dispersed gold, in the desire and libido for gold, the affect from gold, and gold as a drug. Gold is always connected to drugs, something Michael Taussig elaborates on in his My Cocaine Museum. Then there is the amnesia linked to gold, the attempt to put away the violence inherent in it. Gold is always connected directly to violence. The question that interests us here is what kind of culture of amnesia related to gold we have here in this city. And there is the refining of gold, and specifically its psychotropic refining, which we deal with here. The exhibition is not about the commodity trading of gold as such, but more specifically about the refining of gold, although not the refining done in Ticino in the refineries there, but the psychic cleaning, the psychic healing, the psychic refining of the violent narratives of gold.

Dimitrina: It is then pure gold, universal gold.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Opening, 2017-09-10. Photo: knowbotiq

What we bring in here are three different apparatuses, or machines, or assemblages, which help you psychically refine the violence of gold. It’s also about gold and ghostly matters, the ghost of the violence and the traumatic experience linked to gold. The ghosts never go away. You can kick them, but they keep coming back. You thus need new concepts of time. Because the future and the past and the present are very interwoven in gold.

Dimitrina: Gold is timeless. Time out of joint.

Yvonne: You are right. The symbolic and aesthetic dimension of it interests us as artists, its timeless, its purity that is a construction to deal with gold over the centuries. Because gold itself does not lose its materiality, as much as it is melted into bullions, into other shapes.

Alan: A bit like energy with its law of conservation, which can turn from one form into another or be transferred from one object to another, but is never created or destroyed.

Yvonne: Yes, it cannot leave the Earth. There is a constant amount of it on the Earth, a cube of 22 meters by 22 meters by 22 meters, which does not sound like a lot. It’s been that amount since the beginning of the Earth.

Christian: At the same time you don’t know who has it. It wouldn’t be possible to build this cube.

Yvonne: Not only do we not know who has how much of it, but if you look at trading in gold, its volume is much higher than this cube of 22 meters.

This kind of aesthetic and libidinal and also political issues of gold is what we are trying to combine in our project. Not the result of research and statistical diagrammatics of gold. We ask what it is that everybody has a connection to gold. Everybody has some experience in their family, in their life, gold plays a role. Where does this desire of gold come from? We said it’s not only the gold, but also the cultural archive behind gold, which has grown over the centuries, also and especially in Switzerland as a Calvinist country, where gold plays the role of Calvinist money. We try to deal with that in the exhibition with assemblages, associations, music, text, not as a result of our research where we would present a thesis. It’s a speculative thing. Everybody can make contact with something they see in the exhibition. But it’s not a story we want to tell. It’s a kind of a gesture.

Dimitrina: Through the openness of all these machines or assemblages. People can connect to the machines that you generate in the space.

Is there a kind of ideology behind the Calvinist approach to gold? In what way is gold connected to Calvinism?

Yvonne: It’s not ideology. It came from Max Weber and his connecting the Calvinist idea of work and religion. Even if he does not refer to gold in particular. In a Catholic context, gold and money belong to the people, and they have to sacrifice it. Jesus said to the people they could sacrifice money and gold for him, to declare their connection to him. But in a Calvinist or Zwinglian context, money or gold belong to God, and people, mostly men, have to negotiate with God’s money to increase and accumulate it. When he deals with gold or money in a way that makes other people lose, or is connected to violence, he is not guilty, because he works with the understanding that he is multiplying the money of God. That’s what’s behind God’s money. It’s a bit ideological in a way, because you don’t find much about it. It’s a hidden history. But in comparison to the role of God in Catholic communities, the Calvinist handling of gold is not only fiction. Gloria Wekker told the same story, saying in White Innocence that the Netherlands as a small country has a similar historical tradition as Switzerland. Because the Netherlands are so small, they claim they cannot have a significant impact on the global community. They consider themselves innocent. With this wall of innocence, they refuse any accusation of their country’s involvement in the violence of colonialism. The same applies to Switzerland.

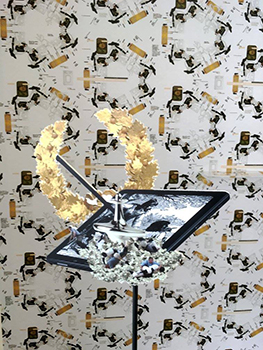

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Exhibition views. Photos: knowbotiq

Dimitrina: Portugal was also small, and what kind of colonial expansion they had! Isn’t it the Catholics who started first, collecting the South American gold and bringing it to Europe. As far as I am aware, that gold never reached Portugal, as it was immediately passed on to Amsterdam, for example. The ships didn’t even stop in Lisbon, but went to England or to the Netherlands.

Yvonne: The ships themselves did not belong to Portugal. They were owned by companies, Swiss, French companies that took part in the trade.

Alan: The Open Veins of Latin America by Eduardo Galeano describes the gold trade at the time as a debt economy, something quite related to what we have now, as described by Christian Marazzi among others. The king’s houses in Spain and Portugal were heavily indebted, particularly to The Netherlands. And that was one of the reasons why even though some of the gold might have been theirs, it went directly to serve the payment of their debt, to whoever they owed it to.

Christian: The exhibition tries to bring the gold question much closer on a micro level, a molecular level, withing our bodies of cultural workers. It’s not about them, about the Swiss. We are not Swiss, and it would be easy to point an accusing finger to the Swiss, the Calvinists. We all live here, and all of our being is based on this richness which is to a great extent built on the gold that was brought here. The Calvinist thinking is also in many of our bodies, through the racist education we have gone through in our lives. In Austria, for instance, I was brought up in a fascist family. Yvonne was more aware, and much earlier than me. Everybody is somehow affected by these different matterings of gold and the meanings of the matter of gold. Here we provide an aesthetic setting which enables on an experiential level to deal with these questions. Not so much with the logos, by naming and addressing and speaking about it, but somehow dealing with it with our bodies, and our wishes to get somehow healed – a problematic term – of the ghosts of the gold molecules that are in the air and in our bodies. The question is then from an artistic point of view how to speak about it, and to whom to address it. We are interested in addressing it to ourselves, to us, to you, to the people involved in the project. How do you deal with it? How do I deal with it? And what do we generally do? And we realized that many of the artists around us deal with animistic questions, with witchcraft, with ghostly matters. Everybody seems to want to get rid of the Enlightenment. Everybody is healing their body, not only in art but also in life, and healing the environment and the plants, or getting healed by the plants. There is this trend now in all these people towards this topic. We wanted to bring in here a kind of machinic assemblage, with practices that do a kind of healing with the violence of gold. And gold is also involved in the practices we bring in here. It’s Meditation on Pure Gold, by Gabriel Flückiger, and Acupuncture (Golden Needles), by Martina Buzzi, and vaporizing golden aphrodisiacs, mostly Viagra, as most of the Viagra names are associated with gold, golden pills, in Diffraction (Golden Aphrodisiac and Truth Serum / Henbane). The sexual machine is also very closely associated with gold.

Yvonne: It’s not only that we want to show this practice. The basis is that we say, gold is so important that everybody has a bodily experience of gold. For me it is that my mother died to years ago, and I got some family jewelry from her. They were very old, and came from my great-grandmother, who was born in slavery, and it was a kind of matrilinear security. The mother passed it on to her daughters. If you get into a bad situation, if you have no husband, or are a widow, the jewelry provides some kind of security. The jewelry itself is also an aesthetic production, bracelets, earrings, rings. Its’ hardly something you’d sell and get money for. The symbolic value of it is much bigger for me than the economic value. At the same time this jewelry is quite old-fashioned. I could not wear it on me in daily life, here. For me, it’s a kind of bodily experience. I saw it on my grandmother. It’s very close to the body. But now, it’s in a bank, locked up there. It has no possibility to tell a story again and again. That’s a kind of aesthetic and the experience that connects me to her. This gold has its history, and it’s not only a symbolic gesture from the mother to the daughter, but had an urgency. In Caribbean families, until the end of slavery, there was no pressure to get married as a woman, which led to many open connections or family situations as a result of slavery. This is why this jewelry was very important for this kind of matriarchate, combined with a lot of violence.

Alan: It’s a kind of matriarchal insurance.

Yvonne: Yes. But it’s not a kind of dowry. Not a deal between the family of the bride and that of the groom. It’s different. It’s from the mother to the daughter. A matrilinear connection. And now it’s stuck in this jewelry, with its old-fashioned, filigree aesthetic. That’s one story I can tell. Everybody has their own. But it’s very close to the body. Our interest is not in statistics and this kind of big financial trading. We want to make it close to the body, also as a practice, with jewelry, gold acupuncture. It’s a kind of history, but also an actual practice of what happens with gold.

Christian: Take the performative setting Meditation on Pure Gold by Raphael Flückiger in the exhibition. Raphael has been involved in shamanistic practices for two years now. In conversations, another person told me that a lot of people are sitting naked on their bullion at home, claiming that the energy of gold is the closest to the human body’s energy. And Martina Buzzi, in Acupuncture (Golden Needles), can stimulate the ghost points in the body, the gui points. So here in the exhibition she will stimulate the gui. In Chinese medicine, each body is possessed by some ghosts, and you have to get rid of those ghosts. You can deal with your ghosts by going to Martina, who will activate your gui points, the ghosts that haunt you. It’s not about representing the healing processes. We want to avoid pointing fingers at someone, and focus on topics within our own bodies. As theoretical doers we are mostly now working on queering matter, on the queering discourse on matter, referring to how Karen Barad localizes difference, which is taken up by Nina Bandi and Anna Frei in their performance Molecular Listening at the opening. Difference is not there; difference is only enacted, by turning and returning the topic of gold, and only by doing the differences within gold you get around it. And this returning is done within bodies and thinking, in the performative settings in the exhibition. This is speculative and risky, so close to turning the questions on gold, on colonial and post-colonial violence in our bodies as cultural workers. We are in the middle of it, and don’t know how far we can get with these machines. We don’t put things on the wall, but in the middle, and you can touch them, sit beside them, very close on the benches, or you can let them get into your bodies, with the needles, or inhale the Viagra kneeling down in a ritual process. The space will transform. From the outside it will look like a Yoga club or a jewelry shop, with two big Buddhas visible from the outside, and shelves with jewelry inside. Corner College goes shamanistic…

Yvonne: For us, fabulation is a way to deal with historical stuff – let’s not call it artistic research, because that is a difficult term –, with some experience in an artistic way. We like the critical fabulation of Saidiya Hartmann. It’s one kind of fabulation. She says it’s important, not only for artists, but more generally, to deal in some other way with archives that are around us. Mostly, with institutional archives, at a national level, as we have them in Switzerland as well, but also with cultural heritage. On the one hand with fixed institutional archives, but also with history or knowledge. According to Hartmann, we have to deal with these in a new way, as a minority, be it black people, or female black people. What is fixed in the archives, according to her, is mostly a paternalistic white view on what has happened. We have to affect what’s inside the archive, what is not explicit in them but can be found between the lines, if you have another gaze on it, another sensitivity. What is written is mostly written by white male people, but there are other histories, and we have to find them by means of critical fabulation. As a consequence, you could change history. That’s not what we want. We link this understanding of archives to Gloria Wekker, or Edward Said, who also speaks of cultural archives. Everything could be an archive. Oral history is a kind of archive. But also plants and stones and animals can be archives. Uriel Orlow works with the latent archives in plants when he deals with the history of Apartheid in South Africa. We are not following down that path. Our topic is gold. But gold is refined, and everybody says it’s only gold, 99.9% pure. But we know it’s full of history. It’s a kind of violence that is stored in it. How to deal with that kind of ghosts inside the gold, how to affect, how to expose this, call it out, that’s the way of ghosts, ghostly matter. A lot of history is not written, not decoded by the historian, and so we have these kinds of personal ghosts, collective ghosts, and we have to find other ways to deal with them. This is the hauntology we pick up as a historical practice. That’s what we try to do with gold, with our opulent assemblages.

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Exhibition views. Photos: knowbotiq

Dimitrina: Is it inside the gold, or rather an aura around the gold.

Yvonne: If you go to a very molecular level, and that’s the speculation and fabulation, maybe there is a situation that’s inside. In a way, they are searching for it. The declaration of gold is getting ever more specific. Scientists will be able, in some time, to determine the provenance of gold by analyzing what other elements are in it.

Alan: Even after refining. So the text has been erased, the violence has been erased, by refining the gold, but not sufficiently because the methods for looking at the gold are becoming better, too.

Yvonne: Yes, and that’s the technological part of this. Everything goes more and more into the molecular. And it’s not just the physics, the construction of atoms. It’s also libidinal. Gold is connected to desire. It’s always that which people want, and it goes over borders of violence to get the gold. This libidinal element is also part of the molecular aspects of gold that we are interested in. In terms of technology, as Christian mentioned, gold is also used in biolistic gene guns as a small molecular vector to insert DNA snippets into a DNA strand. Gold itself makes a new assemblage of this, but it remains, as it cannot disappear. In plants there are gold particles, and techniques have been developed now to extract that gold. That’s the motor of technology, to find a way to extract it. It was also a kind of war strategy. Adolf Hitler had a research program to extract gold from salt water. He built a huge factory to do that. But the energy that had to be put into it was too much for the gold that could be extracted. Gold has always been a driver of violence and technological evolution. That interests us, at a very molecular level. This kind of gold mining, and what happens now in gold mining, also in my mother country Suriname, it’s a lovely country, and they tried a lot to build conditions for ecological tourism, but now the gold industry is starting, and the country itself, or the people who live there, see that it will take just twenty years, and all the rain forest and all indigenous people will have vanished, all because of this desire of gold. So we have this very macro level, but also the tiny molecular level. And this molecular level is what interests us here.

Dimitrina: It seems like a paradox, of gold as commons in some way, in the circuit of everything, as it’s in the water, in the plants, in the bodies, in Earth itself, and also part of the desiring flows, and then there is capitalism and how it appropriates and accumulates, using violence to force the accumulation and appropriation of gold from everywhere.

Yvonne: It’s a different situation when you deal with that in Switzerland, where there is a lot of money and a lot of gold. In this Calvinist situation that Christian talked about, people do not want to show their money, or their gold. Sometimes as jewelry, or as a watch. On the other hand, in this huge industry of the esoteric, gold is a huge player. In spa situations, in these esoteric situations of meditation, at the really high level, in exclusive strategies, gold is involved. Thus, meditation on gold, acupuncture with gold, gold pills, gold masks in the spa, you can eat gold, put it on your skin, under your skin. At the top levels of treatment, gold is always involved. It’s mostly obvious in the Swiss cosmetics industry, in La Prairie, a company from Montreux, which sell one pot of skin care for 600 to 800 Swiss Francs. Their advertizing does not say it’s good for your collagen or something, but they deal with this very ephemeral aesthetic language about eternity, purity, it came from the mountains, it makes you eternally young, and at that moment there is a special language, a special, totally exclusive aesthetics involving gold, for a very small number of people. That is where we are in Switzerland. For us, it’s not that we said we want to point fingers. It’s part of the way of living in Switzerland. This kind of esoteric practices like meditation, acupuncture, the dispersion of this molecular substance, has two different strategies. You can say it’s exclusive, for a small number of privileged people. On the other hand, there are connections to these practices also in other cultures, where the mediation or acupuncture came from, where it is also for all the people. It had a great impact on dealing with healing strategies, and cannot be demonized. This ambivalence is interesting to us. It’s a kind of privileged strategies, thinking I’m only in me, and don’t want to see what is happening outside of me. At the same time, these practices also offer the possibility, as Christian mentioned about the gui, to deal with traumas. Meditation and acupuncture deal with demons inside the people. And it’s not only the personal demons but also the collective, historical demons. These practices are for us also about dealing with the post-colonial, collective way of being guilty in history. It’s very speculative, because we have no research about it. For us, dealing with gold, we are trying a way, at this moment, at the molecular level, of the hauntology, and the collective traumas. But we don’t know what would be further steps from here.

Dimitrina: For me it’s also interesting how the vital force of gold, vital in the sense that it’s something inorganic, but at the same time involved in such vital forces as healing, enters how you deal not only with the economic impact of gold but how it transforms into a bio-force. In the ancient world they produced golden chalices for drinking, but also Pharaos’ death masks, an inorganic molecule between death and life and can pass through the bodies, all this connects in my mind to what you have been saying. Gold is infusing, going through the bodies, the flesh, organic matter.

Alan: I’d like to know more about the role of your research. You have some, not complete, not about everything, you explore some context, and then you say it’s not really commodity trading as such that you want to address, but more libidinal forces.

Dimitrina: This is also kind of connected, to what extent our bodies are connected to capitalist accumulation, because it’s very bio-form, not something that is just a metastructure, from what I understand of what you said. It’s not about economic fluxes independent from the bodies. They cross the bodies. Everything is connected at a molecular level.

Yvonne: There is some research. That’s why we are interested in working with sociologists like Rohit Jain. We discussed that, and for him it’s also important to make a connection to the public. It’s not only that we do a kind of aesthetic research that is to remain inside this exhibition space. It’s important to go out and do discussions. The exhibition is only a part of our articulation.

Dimitrina: A temporal moment of actualization that will reshape itself in other forms.

Yvonne: And with other partners. We already had one exhibition project at Förrlibuck as part of Draft conference. That was much closer to the research we had done on commodity trading of gold in Switzerland. There are interesting parallelisms. Afterwards, when we did the exhibition at Förrlibuckstrasse 78, we found out that the building had been an office for gold trading before. We didn’t know that before. It was the same place where the Master exhibitions had taken place for five years. We actually wanted to do the exhibition in the Börse, but that was not possible. That’s hauntology in another way. For ten or twenty years they have not been able to rent out this office.

Alan: There’s some ghosts in there…

knowbotiq, The Swiss Psychotropic Gold Refining. what is your mission? Exhibition view. Photo: knowbotiq